On a recent visit to the Queensland Art Gallery I was intrigued by a number of images and realised that they reminded me of works by other artists.

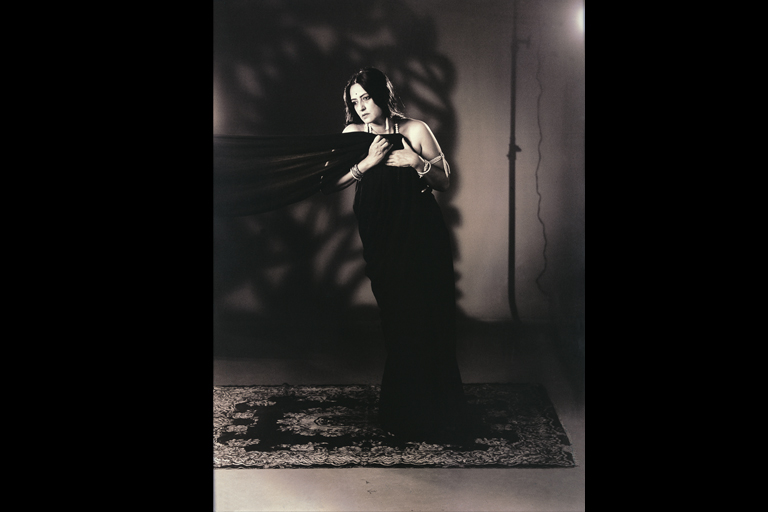

First up was a small group of photographs in the Asian section which I found striking in their simplicity and in the power of their gaze. They were by an Indian photographer – Pushpalama N, – whom I’d never heard of – whose images are very much like those of Cindy Sherman. And like Sherman, Pushpalama N. explores narrative figuration and uses herself as the model, in a variety of guises.

She was born in 1956 in Bangalore and originally trained as a sculptor then went on to work in performance photography and film using elements of popular culture to explore place, gender, history. According to artsy.net, Pushpalama N. is a “photo-and video-performance artists [who] plays the subject in images that critique female stereotypes in India and the reductive classifications furthered by ethnographic documentation.” Hmmm. Not sure what that means but essentially she re-enacts historical representations of women in order to subvert them. Just like Cindy Sherman.

No matter the text (or for that matter the sub-text), the works are striking and powerful and well worth checking out. I have to praise the curator of this little show for the strength and vision here; I browsed the web for images of Pushpalama’s work to illustrate this blog and mostly I was unimpressed with what I saw. But the selection of black and white photographs at QAG is quite stunning and well worth a look.

Cindy Sherman

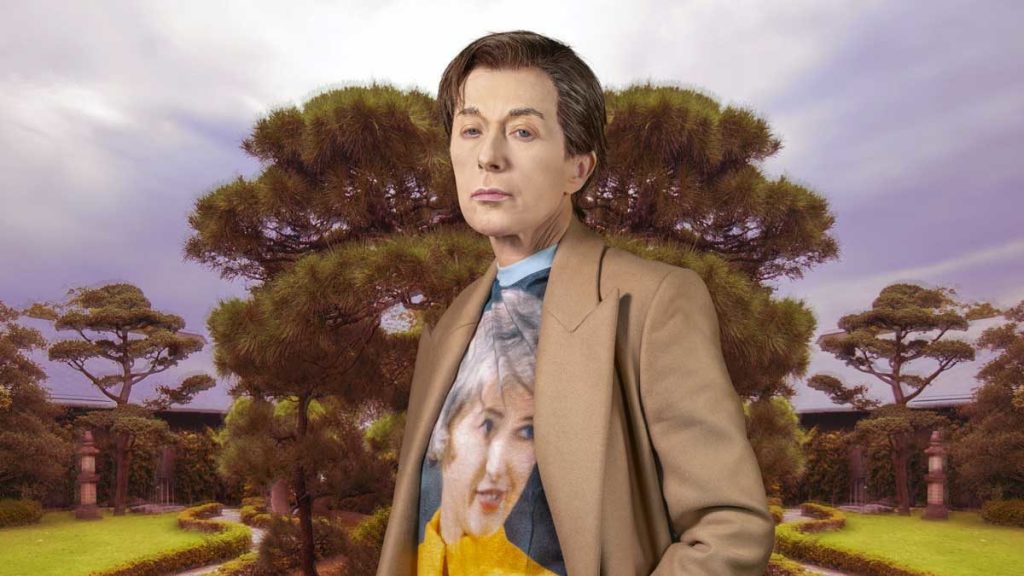

There’s a large show of recent Cindy Sherman works at QAGOMA which I had seen on a previous visit but had to see again. I’m a Cindy Sherman fan; her earlier photographs remind me of stills from film noir but more than that I’m fascinated by her craft: her skill in creating narratives and in transforming herself into highly constructed character studies. They are performance pieces. Interestingly, according to QAGOMA, “Cindy Sherman is one of the most recognised and influential artists of our time”. Yet no-one really knows what Sherman looks like. She uses herself as a model for all her works, but through the use costumes, makeup, prosthetics (and more recently digital photography) Sherman transforms herself into highly stylised characters. There are no depictions of Cindy Sherman.

The images in this current show are very different to previous ones – in content, scale and in Sherman’s use of digital technology, especially Photoshop. But the biting satire and commentary are still there. There is a wonderful series of 5 metre-tall ‘society portraits’ from 2008, and two rather subversive fashion house collaborations, the Vogue-commissioned ‘Balenciaga’ 2007–08, and ‘Chanel’ 2010–2013 in which Sherman clothes her everyday women in haute couture, placing them in incongruous settings. They’re not fashionable or stylish and the result makes you re-think the whole notion of ‘fashion’, of who it’s for and how it ends up. It’s also a commentary on our society’s fascination with aspiration, narcissism and the cult of celebrity.”

Sally Gabori

The other works that impressed me (and that I had to come back for another look) are by Mirdidingkingathi Juwarnda Sally Gabori (my spellcheck’s having difficulty here so I’ll refer to her as Sally Gabori), a Kaiadilt woman (from the Gulf of Carpentaria, off north-western Queensland) who began painting at the age of 81.

Large intensely coloured canvas, bright and block like. Powerful images. This was new indigienous art and I was impressed. I’m not sure that anyone’s really game to talk about indiginous art except in very traditional non-formal terms. For some reason (the ovious ones) aboriginal/indigenous art isn’t scrutinised and critiqued in the same way as other art. What I found so refreshing about these works was not just their vibrant palette but their intensity and the way the paint was applied – not a dot or line to be seen – let alone a smudge of ochre. It was almost colour-field and indeed reminded me very much of the huge fluid painting of Helen Frankenthaler. Interestingly, the little extended labels (the things that people most usually look at longer than the art work) said not a thing about the construction of the work. Instead it was all about ‘country’. I didn’t really understand what the relationship of country was to the visual representations on these framed canvases but I was keen to find out.

This exhibition is a retrospective; it includes her early paintings, her large collaborative works with other Kaiadilt women, and her almost monochromatic recent paintings and works on paper. The experts say that the paintings are “depictions of her homeland …. abstract in nature, but retain representational elements which map traditional country and cultural identity in monumental paintings.”[Jeremy Eccles,SMH] One thing is certain: in both the design and the boldness of her colour Gabori’s work is unique in Aboriginal art.

What’s striking to me is the (apparent) lack of traditional iconography (though again, I think it’s interesting that the labels speak about country rather than the painting). Nicholas Evans in his obituary in The Australian wrote that: “Beyond the names she gave them, Gabori was reticent about revealing the exact interpretation of her paintings. My view is that they are worked up from distinctive blocks of light or colour, emanating from the land and sea at the locations she names; the landscapes are transmuted so radically that they are barely recognisable.”

So why can’t we just read them as abstract paintings and critique them in the same way we do other similar (i.e. abstract) works? I suspect it’s the artistic equivalence of political correctness. Interestingly, there is a painting by Australian abstract artist Tony Tuckson just around the corner from the Gabori, and if you didn’t know you’d be forgiven for thinking it was a Gabori painting. I was (again) struck by the similarities. And again, I have to wonder: why can’t we talk about these works within the same terms of reference? They’re clearly very similar. Ah, the art world. When it adopts political correctness, it’s anyone’s guess.

And finally, a piece that made me laugh out loud (particularly in its quotidian pasticheness) was a 3-D glass and metal sculpture in situ outside the art gallery: a mini pyramid, paying homage to The Louvre’s Pyramid. l I have no idea of who this is by – or for that matter, what it is – but I thought it was imminently fitting that it was there.

So next time you’re in sunny Queensland wandering what to do – go take a wonder around the galleries. You’ll be surprised at what you find.