Lieutenant Captain Titov sat in a cramped prison cell with about twenty other men, most of them fellow officers of the White Army as well as a middle-aged priest. It was 1922 and Timofey Titov was 27 years old. He had been serving under Admiral Kolchack in the Russian Civil War on a submarine in Vladivostock. He had been arrested by Red soldiers and was now facing execution. One by one the men were called and led out of the cell. The sound of boots crunching on gravel, shouts and gunfire, boomed beyond the walls. Finally, there remained only he and the priest. Titov was a devout Orthodox and asked the priest for absolution. He knelt and prayed. Then the priest too was taken away and Titov sat on his own, his execution looming nearer. When the cell door opened, he was prepared for his fate. He only wished that he could have said goodbye to his wife. A soldier walked in and called his name: “Timofey!” Titov looked up and gave a cry of surprise. Standing before him was one of his former soldiers. But in a Red Army uniform. He motioned to Titov to be quiet and told him that although he had changed sides, he was still loyal to his commander and that he would help him. He asked him if he would provide information about himself, his date of birth, rank, and a brief outline of his life. Titov consented and was given pen and paper. The soldier then told him that he would come back when it was time for the changing of the guard. Titov should quickly go out into the yard and then through the main gates which would be open. “They won’t notice you in all the confusion,” he said, “but you have to be quick. You only have 12 hours to be gone out of Vladivostock. After that they’ll notice you’ve gone and send out a search party to arrest you.” On a small scrap of paper, he wrote down the name of a Chinese man who would guide him across the border.

And so, with the changing of the guard the soldier came and opened the cell door and motioned to Titov who walked quickly out of his cell and out of the yard and then ran all the way home. He briefly told his wife, Marina, what had happened, saying that he would explain everything later, but now they had to leave. He made it clear that she didn’t need to go with him, that she would be risking all. Marina agreed to go without hesitation. They had to wait until it was well and truly dark before setting out. Marina put on two sets of clothes and her fur coat. Her mother gathered some gold and jewellery and tied it into a handkerchief telling Marina to put it into her girdle. She gave her an icon (which is still in the family), kissed Marina and Timofey and wished them God speed.

The Chinese guide led them stealthily across the border into Manchuria where another Chinese man helped them to Harbin. It was a journey of some 880 kms and took them weeks to complete. Marina never saw her mother or family again.

So began the story of my maternal grandparents’ flight into Harbin and their life in exile. This story, told to me by my mother, was the one that sparked my interest in my family history. Prior to this I had only a vague understanding of what a “White Russian” was.

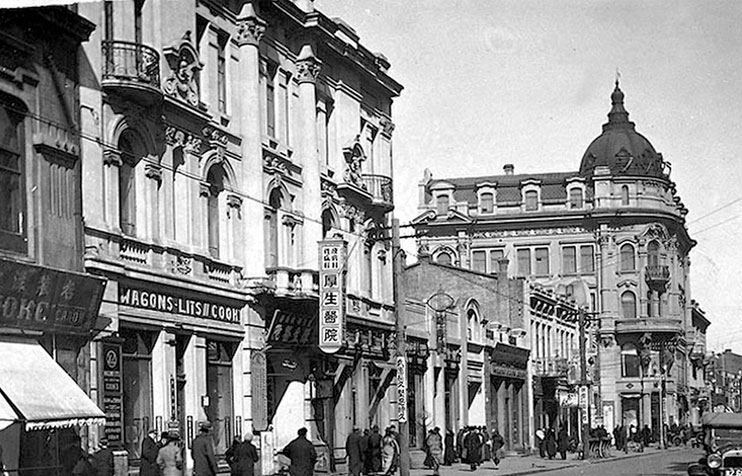

When I was in secondary school the Headmistress once asked me if my family were White Russians. I didn’t know what she meant. Yes, they were Russians, and they weren’t dark-skinned….so yes, they were White Russians. She asked if they were from Petersburg. I said no, Harbin. “Ah,” she said, “an interesting history.” At the time I didn’t know that Harbin was an unusual place. I actually didn’t know anything about Harbin. I had no idea that it had been a little microcosm of pre-revolutionary Russianness in Manchuria. When asked where my parents were born, I would say that my mother was born in China. This was always met with scepticism and the comment that I didn’t look Chinese. This is the routine response with which all children of Harbin Russians are met. I would state that either my grandmother or my grandfather was Chinese whilst the other was Russian. It seemed easier than trying to explain. No-one has ever questioned me about this.

Hearing about my grandparents’ flight to Harbin sparked me to think that this was not a usual kind of history and that it should be preserved. It also occurred to me that my mother was the keeper of this narrative and being in her 80s, this narrative, if not documented would disappear and with it, not only my own family’s history but so too the history of Harbin Russians in Australia (as most of them came out as young adults in the late 1950s.) Those who were younger claim they were too young to know anything about what was going on at the time so were not in a position to be advocates for this history.

I came to realise that it was a history that was little known by other Russians as well. I had recently met a few Russians who had emigrated in the last 10 years or so from Russia and when I told them about my mother being a Russian from Harbin, they had no idea of what that meant. Harbin’s history – the history of the White opposition to the communist Revolution and Stalin’s Soviet Union – had been eradicated from the Soviet Union’s version of Russian history.

Russian memories are thus divided between two Russias: the Soviet Union and Russian émigres. The émigres created sites of memories[1] to assert their connections to the Russian past and remind people not to forget them and their version of Russian history, whereas Soviet Russia – through its journalists and propaganda – sought to sever the USSR from the Russian past and separate the first socialist society from its enemies in the present.

The selective memory of life in an idealised pre-revolutionary Russia helped Russian émigrés cope with the experience of exile, and of living within a liminal state. These Russians outside Russia developed their own narratives of Russian history, memories that countered the centrality of the Soviet experience and denied the legitimacy of the Bolshevik government.

In China, Harbin’s history has similarly been redacted. The last of the White Russian emigres left China in the 1960s. Manchuria, is no longer. The Chinese Communist Party took over the province and it is now known as the region of northeastern China, covering the provinces of Liaoning (south), Jilin (central), and Heilongjiang (north). Harbin is now the capital of Heilongjiang.

The many churches that once graced Harbin have disappeared – the iconic wooden St Nicholas Cathedral built in 1900 without a single nail was desecrated and pulled down by young revolutionary Chinese Red Guards in 1966. St Nicholas had stood as a powerful symbol of Russian presence, both physically and spiritually, in the middle of the square opposite the Railway Station, which also has been remodelled. Another major Russian site, St Sophia, built in 1907 was also closed during the Great Leap forward (1958-62) and then turned into a museum in 1997.

More dishearteningly, Russian cemeteries have been bulldozed and headstones used for paving. This desecration has been a shocking discovery for some former Harbiners who returned to Harbin, finding themselves walking on the headstones of their ancestors. The vestiges of Harbin – once a thriving Russian city with Russian shops and Russian street signs – remain only as museum pieces, as remnants of a quixotic enterprise.

The Chinese do not acknowledge Russia’s role in the construction and development of Harbin. Nor do they acknowledge the date of Harbin’s construction (1898). The fact that the Russians built the Chinese Eastern Railway from Siberia, across northern inner Manchuria via Harbin to Vladivostock, without which China could not have prospered and developed its rich resources, are not mentioned. Instead, the revisionism of Harbin locates it as a Chinese city, complete with new archaeological findings to prove its provenance. We Qu, editor of “The Jews in Harbin”, masterfully changed history by saying that “Harbin has a long history that goes back 5000 years.” For them, Harbin was always a Chinese city with Chinese presence. Their refutation of its colonial past extends to not acknowledging the centennial of Harbin in 1998.

Historical revisionism is also evident in a memorial to Soviet soldiers which was quickly constructed at the Harbin Huangshan Russian Orthodox Cemetery in October 2007. It contains a large monument and many identical “graves” with red-starred tombstones (presuming to bear the names of Russian soldiers who died while attempting to overthrow the Japanese and liberate the Chinese in 1945). This Russian War Memorial Cemetery was completed in just two weeks following the signing of a joint strategic document between Russia, China and India in the first week of October 2007. It was in effect a tacit revision of history by both the Russian Foreign Minister who approved the construction/development and the Chinese. The irony of this isn’t lost on former Harbiners who know that the Soviets had banned Russian Orthodox religion.

Is there such a thing as objective history? The veracity of history is never clear. It comprises infinite numbers of variables that can be included or discarded. It also depends on who is writing that history. The contrivance of history is aptly summarised by migration scholar Carl Becker as “an unstable pattern of remembered things redesigned and newly coloured to suit the convenience of those who make use of it.”[2]

In my research – which aims to provide agency to the lived experience of Harbiners in Australia, I have relied on questionnaires, interviews, memoirs and published articles alongside scholarly texts. However, the reliability of historical memoirs and narratives presents a challenge in the construction of this narrative. Memories are fallible. My interviewees are ageing. Things are not always clearly remembered. And the personal histories are subject to nostalgia which blurs the discomforts of reality into a more acceptable version of the past. They often omit the uncomfortable aspects such as for instance, anti-Semitic and fascist conflicts, the horrors of the Japanese occupation; the terror of the Soviet SMERSH (an arm of the KGB) under Soviet “liberation,” the imprisonment and execution of former White army soldiers and officers or anyone who collaborated with the Japanese, whether voluntarily or not.

Historian Dan Ben-Canaan uses the term “historical reality” to counter the subjective or nostalgic or indeed the political versions of history. He states:

Historical reality deals with the actuality of existence. It is not fiction. There is no concern with the prettification of what was not with its ugliness. It is a presentation of the past as is, as it was.[3]

My aim is not to construct a history of former Harbin but to interrogate the historiography and to provide some nuance to that history through the lived experiences of these former Harbiners. I believe that history is both the objective rendering of facts and the subjective narratives of the lived experience. Whilst the facts and figures give us the raw data, the memories of the lived experience provide us with a glimpse of a former life and an insight into difficulties encountered by a generation so very different from our own. They provide us with an understanding of what “identity” means; a glimpse of what it means to hang on tightly to an identity shaped by language, culture and traditions – and indeed, why – or of how to forge a new identity based on new experiences. They also provides insight into how resilient emigres/migrants/refugees are and how valuable their contribution is, by shining a spot-light onto an otherwise un-known culture and place.

[1] Pierre Nora defined these as “Lieux memoire” – memory places – material, symbolic and functional. They are touchstones for the community (and historians) to connect with the past through a connection with place. Pierre Nora, Realms of Memory: The Construction of the French Past. I: Conflicts and Divisions, ed. Lawrence D. Kritzman, trans. Arthur Goldhammer (New York: Columbia University Press), 14.

[2] Carl L. Becker. Everyman His Own Historian: Essays on History and Politics (Chicago Ill.: Quadrangle, 1966), 253-254.

[3] Dan Ben-Canaan, “Nostalgia vs. Historical Reality: Imagined Communities, Imagined History,” The Sino-Israel Research and Study Center. The Harbin Jewish Culture Association, 2014, 6.

[2] Pierre Nora defined these as “Lieux memoire” – memory places – material, symbolic and functional. They are touchstones for the community (and historians) to connect with the past through a connection with place. Pierre Nora, Realms of Memory: The Construction of the French Past. I: Conflicts and Divisions, ed. Lawrence D. Kritzman, trans. Arthur Goldhammer (New York: Columbia University Press), 14.

[1] Carl L. Becker. Everyman His Own Historian: Essays on History and Politics (Chicago Ill.: Quadrangle, 1966), 253-254.

[3] The Memorial Cemetery for the Fallen Russian Soldiers

[4] Carl L. Becker. Everyman His Own Historian: Essays on History and Politics (Chicago Ill.: Quadrangle, 1966), 253-254.

[5] Dan Ben-Canaan, “Nostalgia vs. Historical Reality: Imagined Communities, Imagined History,” The Sino-Israel Research and Study Center. The Harbin Jewish Culture Association, 2014, 6.

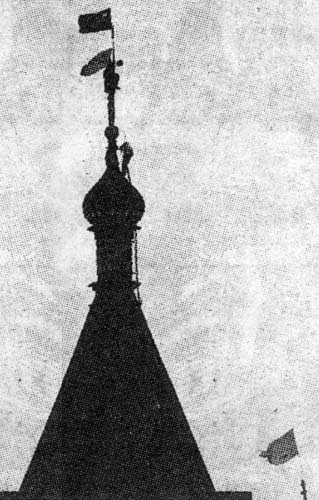

The destruction of St Nicholas by the Chinese Red Guards

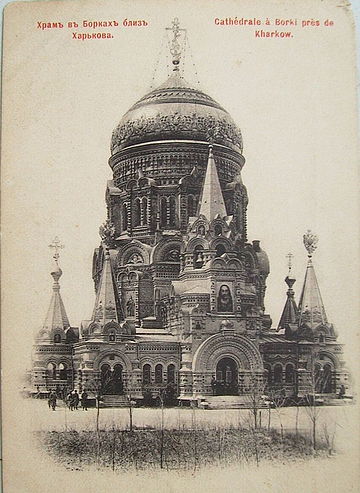

St. Sophia, Harbin

Click here to read the thesis: https://espace.library.uq.edu.au/view/UQ:1344cbc/s4500165_phd_thesis.pdf?dsi_version=7969c44429b18fd747f978e8b5a521b1

HI Tania. I came by accidentally to your thesis which I will read in full. I am fascinated by the history of white Russians and look forward to reading it. My reason for reaching out to you is that I have a lot of photos and historical books of early Harbin. I have other artefacts inherited from my step-father that I would like to donate. Unfortunately, I have been unsuccessful in donating these items or determine if they are of any value. Do you have any suggestions or recommendations? It would be such a shame to bin these items. I am located in Sydney and have contacted several Russian organisations however there has been no interest. Thank you for taking the time to read this email. Kind regards, Anita

Hi Anita,

Thanks for reading. It would be great to have access to your memorabilia. I’m unaware of any archives here but there are quite a few in the US. I’ll contact them to see if they’re interested. There’s a fb site for Russians from China that I’m a member of – I’ll contact them to see if there’s anyone who has access to archives. I’m in the process of setting up an archive at UQ. It could be possible to donate there. I’ll do some research and let you know.

Tania

LikeLike